What we can learn from the Last Ice Area

Published on 21 Oct 2024

The Arctic Ocean’s last ice sanctuary is the focus of intense scientific research. Discover the story of researchers Mathieu Ardyna et Warwick Vincent at the heart of the last ice area.

On the opposite side of the screen, Mathieu Ardyna keeps freezing. The connection on board the Canadian research icebreaker CCGS Amundsen, somewhere off of Greenland, is poor. It takes several attempts before we are able to speak with the scientist returning from the REFUGE-ARCTIC expedition. This international, multidisciplinary research program has collected data in the last ice area in the High Arctic. “We want to establish a baseline of the interactions between sea ice, the air and the ocean in this region, which is one of the least explored in the world,” explains the project’s principal investigator.

Credit: Amundsen Science

The oceanic region at the northernmost tip of Canada and Greenland is bearing the brunt of global warming, which is four times faster in the Arctic than in the rest of the world1. As a result, the “old” sea ice that is normally present here all year round, even in summer, could eventually disappear. From small ice algae to Arctic cod, seals and polar bears, many species that depend on this environment for their survival will face considerable challenges. As for the Inuit, their traditional way of life, based on subsistence hunting, will be threatened.

Time is of the essence; we need to characterize this unique refuge while there is still time. For REFUGE-ARCTIC’s 55 scientists, it is a race against the clock. During a 56-day mission on the CCGS Amundsen in August and September, teams documented the fjords that cover the Nares Strait in the region of Tuvaijuittuq, meaning “the place where the ice never melts” in Inuktitut. “We worked around the clock to optimize every second of our time in these hard-to-reach waters,” says Mathieu Ardyna, affiliated with the Takuvik research laboratory (CNRS/Université Laval).

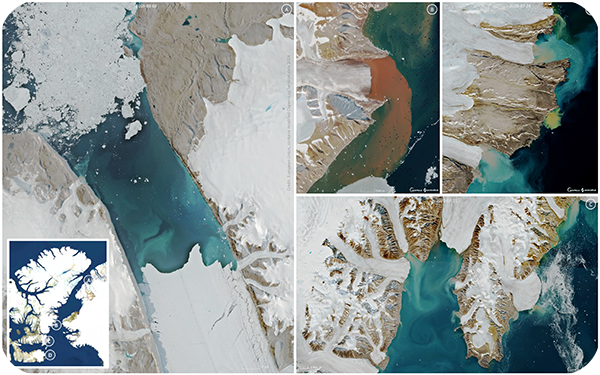

Legend: Marine-terminating glaciers, land-terminating glaciers and ocean interactions. Images taken by Sentinel-2.

Credit: Karen Nieto

“REFUGE-ARCTIC, like so many other projects funded by Sentinel North over the years, is a wonderful springboard for the next generation of Arctic researchers. It’s an incredible training opportunity in the life of a student researcher,” says Warwick Vincent, Associate Professor in the Biology Department at Université Laval and a specialist in the microbial communities that inhabit polar streams.

Undeniable relevance

The never-before-seen samples brought back from the last ice area are invaluable. These include atmospheric particles, sediment and ice cores, benthic and pelagic organisms which, once back in port, are sent to the laboratories in the home countries of the consortium members (France, Canada, the United States, Denmark, etc.). Some of these will be used to study life invisible to the naked eye in high-latitude ecosystems. Because they are under-explored, we know little or nothing about them.

“We often think of large polar mammals when it comes to the Far North, but there’s a whole community of microscopic organisms that support the base levels of food webs. And we’re only just beginning to understand the nature of this aquatic life and how it’s reacting to the rapid changes in its environment,” explains Warwick Vincent. Among other things, the professor has, with his students and collaborators, contributed to the discovery of a new class of bacteria endemic to certain lakes in the last ice area: Candidatus Tariuqbacter. “Tariuq means salt water in Inuktitut,” he specifies.

Credit: Denis Sarrazin

His work on the microbial species that specifically inhabit the last ice area has helped conservation efforts in this sanctuary. Warwick Vincent was one of the scientific advisors involved in the 2019 creation of the Tuvaijuittuq Marine Protected Area, which covers almost 320,000 km2 and aims to preserve a large part of the High Arctic sea ice ecosystem. “The permanent protection of the last ice area requires an evidence-based approach,” stresses Warwick Vincent, who has worked with local Indigenous communities, including those of Grise Fiord, to develop conservation plans for this region.

A legacy

The scope of work on the last ice area goes beyond the hundreds of scientific articles that will emanate from it over the coming years. The knowledge generated will be used, among other things, to ensure the long-term survival of the Tuvaijuittuq Marine Protected Area and the adjacent terrestrial zone of Quttinirpaaq National Park. These concrete outcomes will facilitate the work of future research teams, ultimately helping to predict and better prepare for global changes.

“Sentinel North is enabling us to bring large-scale projects to fruition,” insists Mathieu Ardyna. “This scientific and social adventure has meant positive outcomes for everyone,” adds Warwick Vincent. “We’ve only just begun to fully understand this legacy, which will be felt for decades to come.”