Drawing on neurobiology to fight chronic stress

Published on 4 Dec 2024

An observation is gaining more and more ground in the scientific community: to diagnose and treat chronic stress and mood disorders, we need to look beyond the black box of the brain. It appears that other systems of the human body and living conditions could play a decisive role in the equation.

In short, this is what Caroline Ménard, who holds the Sentinel North Research Chair in the Neurobiology of Stress and Resilience, and her team are examining. “Our focus is on the biological factors that control stress response, and more importantly what makes some people more vulnerable and others more resilient,” the researcher explains.

A global scourge

The most common consequence of chronic stress is major depressive disorder, a leading cause of disability in the world1. Even today, in 2024, depression is diagnosed based solely on self-reported symptoms provided by completing questionnaires. Finding reliable biomarkers would be a game changer. We would be able to identify the individuals at risk of developing mental health conditions and ensure that more effective and appropriate care is provided faster.

The discoveries Caroline Ménard’s Chair has made, as well as those to come, could therefore lead to promising developments. All the more so in a context where over 6.7 million Canadians suffer from a mental disorder, as a study conducted in 2011 has shown2. Among Inuit, the proportion of people who reported that they suffer from clinically significant depressive symptoms is double that of the general Canadian population3. And understandably: The North is undergoing major socio-economic, cultural and environmental upheavals which cause a unique form of stress in the people who live there.

Legend: Caroline Ménard presenting her work at the Sentinel North Scientific Meeting in 2022. She will be discussing her latest advances at the final edition in 2025!

Credit: Pub photo

Tracking tiny holes

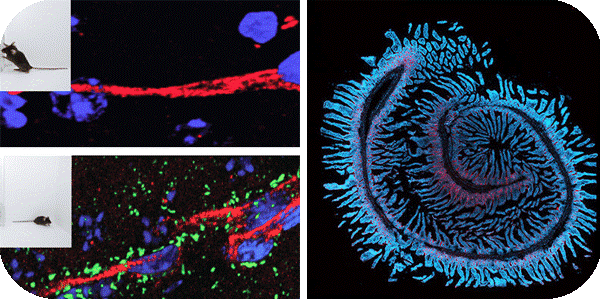

The research team pursues several leads, one of which is inflammation and the overactivity of the immune system when we are facing challenges. Indeed, chronic stress is linked to an increase in inflammatory signals in the bloodstream, and prolonged inflammation can weaken the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which protects the brain against harmful bacteria and toxins. This barrier cannot repair itself properly if it is under constant stress, and this leads to tiny holes that allow inflammation to pass from the blood and reach the brain.

Their research also allowed them to identify molecular and cellular changes in the BBB associated with stress resilience. These changes could play a protective role in the neurovascular system — which underlines the importance of studying not only the pathologies caused by stress but also the positive adaptations in order to better treat mood disorders and increase resilience.

After the neurovascular system, the researchers turned their attention to the digestive system and his gut barrier. After chronic stress exposure, small holes were also observed in this barrier protecting the intestine and preventing inflammation from leaking from the gut into the bloodstream. Moreover, the bacteria profiles found in this organ change when subjected to stress and depression, taking on an inflammatory profile, which could contribute to the elevated circulating inflammation observed in treatment-resistant individuals.

Legend: 1. Blood-brain barrier; 2. Intestinal barrier

Credit: Menard Neuro Lab Gallery

“Our theory is that, in addition to treating the brain, the vascular and immune systems also need to be taken into consideration and regulated, as this could increase the benefits of antidepressants,” the professor adds. She wants to move towards a more personalized medicine in mental health, which would be based on biomarkers as is the case for cancer and heart disease. “There may be specific biomarkers for men and for women, distinctive patterns for different populations, and even according to the type of mood disorder.” This would eventually ensure that diagnoses are more accurate and thus facilitate the choice of treatment.

Olympic-calibre research

As she is called to travel outside Quebec two or three times a month to present her research at conferences and seminars, Caroline Ménard points out that the work of her Chair has aroused the interest of Scandinavian countries in particular, as they face some of the same issues related to Northern regions. In taking an open and interdisciplinary approach to science, the researcher hopes to go “faster, higher, stronger - together, like at the Olympics!”

Legend: Caroline Ménard’s laboratory team

Credit: Frédéric Cantin

Leading the Sentinel North Research Chair has enabled Caroline Ménard to recruit students who come from, in equal proportions, Europe, South America and Canada. They specialize in disciplines as diverse as medicine, psychology, mathematics, engineering, biophotonics and neuroscience. “By giving them opportunities to work as a team, we are able to take projects to greater heights, and make them more creative because everyone brings their own unique skills and ideas to the table, while the students emerge from their experience better equipped on the technical, conceptual and human levels,” the researcher points out.

The work of her Chair is a prime example showing that interdisciplinarity is a rich and innovative approach that enables knowledge to cross all boundaries.

References:

1 Vos et al., 2020

2 Smetanin et al., 2011

3 Mental health and wellness Qanuilirpitaa?, 2017